May 26, 2015 report

Pheromones produced by gut bacteria found to kill resistant variants of its own kind

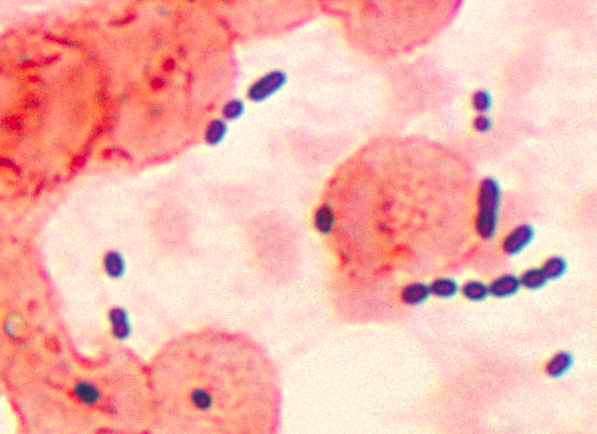

(Phys.org)—A team of researchers with members from Harvard Medical School and the University of Kansas has found that pheromones produced by one type of non-resistant bacteria can kill other bacteria that have grown resistant to agents meant to kill them. In their paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team describes how they discovered such occurrences while investigating mobile elements and metabolic pathways of resistant bacteria.

Over the past decade it has become clear to scientists that bacteria are winning the war against them by us humans—as we develop new agents to kill them, they develop new ways to avoid being killed by them, some of which include mobile elements that encode virulence and antibiotic resistance traits and new metabolic pathways. In this new effort, the researchers were investigating the ways that bacteria evolve to cause themselves to become resistant to new antibiotics, when they discovered that one strain of human gut bacteria, Enterococcus, produces a pheromone that is lethal to other strains of the same type of bacteria.

More specifically, they found that a non-resistant strain of Enterococcus (which is native to the human gut) produced a pheromone called cOB1—when drug resistant E. faecalis V583 bacteria were exposed to that pheromone, they were killed. This finding is important because it shows that native healthy non-resistant bacteria might prove useful in fighting resistant bacterial infections. But more immediately, it shows that it might be possible to use friendly strains of Enterococcus right away to stop resistant bacterial infections in the gut. E. faecalis V583 are a leading cause of hospital acquired infections—they tend to move in to the gut when patients are given antibiotics to ward off infections after surgery and incidentally kill off all or most of the gut biota. This new work suggests such a problem might be averted by simply feeding surgical patients a liquid chock full of healthy bacteria, possibly taken from their own gut, prior to surgery.

The team notes that normally E. faecalis V583 are unable to compete with the healthy strains of Enterococcus, because they have a number of mobile genetic elements in their genome that likely hinder their ability to compete with native bacteria—in the absence of antibiotics. It is only when antibiotics are introduced that E. faecalis V583 gain an advantage and multiply rapidly, causing a gut infection.

More information: Pheromone killing of multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecalis V583 by native commensal strains, PNAS, www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1500553112

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

© 2015 Phys.org