Matchmaking corals from different colonies could reduce bleaching events

Breeding together corals that have naturally high heat tolerance and planting them on coral reefs could increase the reefs' resilience to climate change and reduce the impact of bleaching events, according to Dr. James Guest, a coral reef ecologist from Newcastle University, UK. He is studying this 'assisted evolution' approach to coral conservation and examining the risks associated with it.

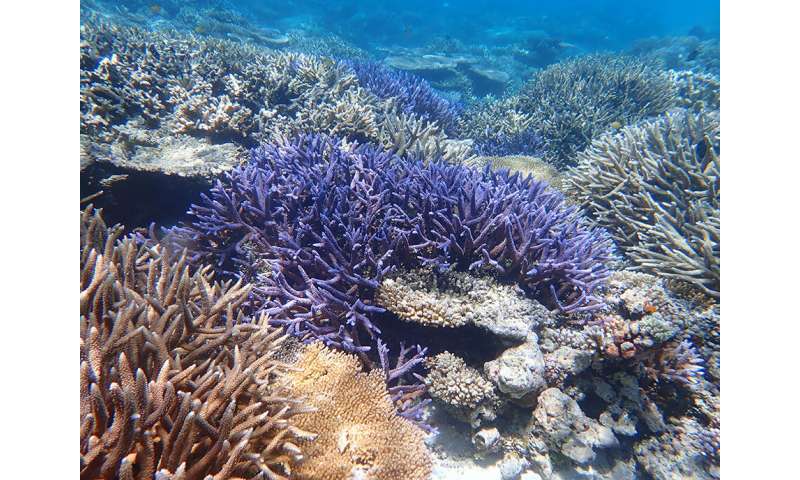

Coral reefs are one of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth, but rising ocean temperatures are causing corals to bleach and then die at massive scales. Dr. Guest belongs to an international team conducting work at Palau International Coral Reef Center in the west Pacific to speed up coral's adaptation to warmer waters by interbreeding naturally heat-tolerant corals to produce offspring better equipped to survive the new ocean conditions. Once outplanted on to reefs, these offspring can increase the heat tolerance of the reef as a whole.

How do you discover which corals are naturally heat tolerant?

"First, we remove about six branches from a tagged adult coral colony. That leaves the colony on the reef still alive, they recover from that really well, quite quickly. We put all those six branches through heat stress tests. Basically, we raise the temperature above the normal range by about 1°C-4°C, we do it quite gradually, and we try to do it the same way that it would happen during a normal heat stress event on the reef. The heat stress test lasts for about 4-6 weeks, it's quite a long experiment, and then we monitor each one, and we see if they bleach and die. In this way we can identify which corals are the most heat tolerant, and which are the least."

And then you begin to breed the most heat tolerant ones?

"When it comes to spawning time, we go back (to the colony on the reef). We look to see if they are ready to spawn and if they are, then we carefully remove them and bring them into the tanks, (to) allow them to spawn there. The corals that we are working with are hermaphrodites, so they have eggs and sperm within one individual.

"We put the individual colonies into a tank and in the aquarium and we try to keep them in really good conditions, with special lights and lots of water flow, so that the colonies stay healthy. They release (eggs and sperm) at very predictable times (usually on full moon night, just after sunset) and then you collect all of the eggs and all of the sperm. We then take the sperm from one colony and mix it with the eggs from another, and vice versa. Last year we did 28 separate crosses from about 8 different colonies, so many different cross combinations."

You call this assisted gene flow. What's the difference between that and selective breeding?

"The definition I've used (of assisted gene flow) means basically the movement of individuals—for example very small baby corals—between populations. It can also mean taking some individuals who have a particular trait, propagating them so that you have more of them and planting them back within the population so that the frequency of that particular trait increases within the population.

"We thought that with (our project) CORALASSIST that we could combine moving or transplanting corals with selective breeding, and see if we can basically increase the number of individuals within a population that are more tolerant to heat stress."

Why is this type of 'assisted evolution' starting to be used to conserve coral reefs and forests in particular?

"They're keystone organisms that make the habitat, and everything in the ecosystem relies on them. If you take the trees out of a forest you don't have a forest anymore, you don't have the space for all of the other diversity, all the insects and birds. It's a similar way with the coral reefs, if you take the corals (out from) there, you still have the rocky substrate, algae can live there and fish can live there but much of the diversity is associated with corals."

What are the risks associated with this kind of research?

"The risk might come with trade-offs, so it might be that the most heat-tolerant corals might grow more slowly or have some other disadvantage we don't know about. We're attempting to test for that by measuring growth rates, and we're looking at their natural survival rates over time in years where bleaching doesn't happen. These approaches are also very expensive to do, so we want to know if they will really have a positive impact on reef conservation.

"It's hard to imagine that there would be any negative effect on the surrounding environment or the overall ecosystem of increasing the frequency of heat-tolerant corals. But obviously what you want to do with all these kinds of things is do trials on them, and keep an eye on them for reasonably long periods of time."

Is there any risk of creating mutant corals, or hybrids that can't reproduce properly?

"It wouldn't be a problem with the approach we are using, because we are breeding things that are breeding with each other naturally. These issues are a potential risk if you're crossing between populations or between species."

Palau, the reefs where you're working, have more or less managed to avoid bleaching events. Why is that?

"There was a big bleaching event in Palau in 1998. That was part of one of the first big global events. They lost a lot of coral, but it's recovered quite well. The corals that are in the lagoons in Palau, they naturally live in an environment where the temperature fluctuations are quite high. Most reefs worldwide do experience some daily fluctuation, but certainly the lagoon corals are quite unusual in that the environment that they live in is fairly extreme. It has low Ph, so the waters are more acidic than usual. But, you know, there's going to be a limit to how much they resist and I very much doubt that Palau can escape the effects of climate change forever."

Are there other ways to improve heat tolerance in corals?

"We are also interested in doing proteomics, which is where you look at protein production, the end stage of the genetic process. When our genes are activated, their job is to produce a protein, and those proteins are the things that carry out the functions of any living organism. We're interested to know whether the more heat-tolerant corals have some special proteins that they produce. Do they produce certain proteins in greater abundance, or certain combinations of proteins that help them to manage this high heat stress?"

Could transplanting these highly heat tolerant corals into the reef solve the issue of coral bleaching once and for all?

"None of these things is a silver bullet. All of the things that we are attempting to do, at best these will buy us a bit more time, and that's why it's so critical to focus on the root cause of the problem, which is carbon emissions and fossil fuels, and also direct impacts like overfishing and pollution, which are all still going on. Those are the most critical things to deal with. What we're trying to do is evaluate this method and then come out with the information at the end and say these are the problems that you might face, here are the costs that are going to be involved, and here are the risks. Then we can give that advice to managers and to policymakers and say, look here's what you could potentially do."

Provided by Horizon: The EU Research & Innovation Magazine