Gene editing could rid sheep of problematic long tails

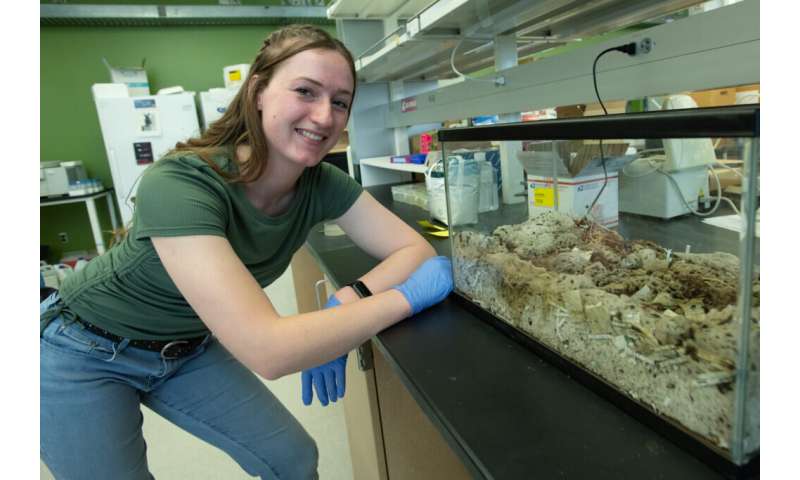

Longer tails have long given sheep producers across the globe problems, but a research project spearheaded by Washington State University graduate student Brietta Latham could eliminate the trait.

While breeds in other regions naturally have short tails, most domestic sheep have longer tails that can lead to hygienic concerns and health issues, including fly strike, a painful and potentially deadly condition caused by blowflies that lay their eggs on sheep. The industry standard has been to dock the animals' tails, which can be painful for the sheep and time-consuming and costly for producers.

Latham was recently awarded a three-year fellowship by the United States Department of Agriculture for her proposal to develop a gene editing strategy to shorten the tails of Suffolk sheep and eliminate the need for tail docking. Suffolk sheep are one of the most widely produced sheep in the U.S.

"Our research will give the industry an alternative to tail docking and improve the animal welfare of our food production systems," Latham said. "It will also improve production efficiency in that we don't have to go through the costs and the labor associated with removing tails."

Humans have been influencing genetics for centuries to select for desirable traits in both plants and animals. Traditionally, this has been accomplished through selective breeding, which can take generations to achieve the desired results. Latham, in her second year of doctoral studies under Professor Jon Oatley in WSU's School of Molecular Biosciences, plans to accomplish this in a fraction of the time.

"Genetic modification has been happening since we started raising animals domestically—anytime we choose to breed one animal with another animal to improve a certain production trait, that is us performing genetic selection," Latham said. "We're really just speeding up the process by using gene editing tools in the lab."

With CRISPR-Cas9, researchers like Latham can precisely edit specific sections of a cell's genome by removing, adding or altering genes.

Earlier genetic research identified the gene suspected to be responsible for tail length in sheep. Latham plans to knock out or remove that gene in the embryos of sheep with long tails and replace it with the gene found in short-tailed breeds. She has used her strategy to successfully shorten tails in mice.

"This is a modification that already exists in sheep. We're just taking this edit that we see occurring in short-tail sheep in China and Iran and we're putting that into the sheep of European descent that have long tails," Latham said.

The edited embryos will be transferred into female sheep, which, after a five-month gestation period, should give birth to healthy lambs with short tails. Those lambs should be able to pass on the desired trait to their offspring.

"The biggest thing with gene editing is making sure we get what we call germline transmission. We want the edits to show up in the gametes, the eggs and sperm that the edited animal is making," she said. "That's how we get transmission from generation to generation."

People often incorrectly confuse gene editing with the more controversial genetic modification through transgenesis. Gene editing does not combine DNA from other species or attempt to create anything that would never happen in nature. Instead, gene editing seeks to bring about desirable changes in an animal species that could occur naturally but may take decades using selective breeding.

"This is a modification that's seen naturally in sheep that people are eating," Latham said, "so we know it is safe to put into the animals and that it's not going to harm them or the people who are consuming them."

Provided by Washington State University