Heading to the North Atlantic to study the world's largest waterfall

The largest waterfall in the world is underwater and is located in the Denmark Strait, between Iceland and Greenland. It is more than three kilometres high and it has a flow of cold, dense water that exceeds three million cubic meters per second. This gigantic current is generated in the Arctic, where surface water cools, gains density and sinks, and makes its way to lower latitudes, following the topography of the seabed. The submarine relief of the Denmark Strait—which in a few kilometres goes from 500 meters to more than 3,000 meters deep—causes this bottom current to accelerate and overflow in the form of an underwater waterfall until it reaches the great troughs of the northern Atlantic Ocean.

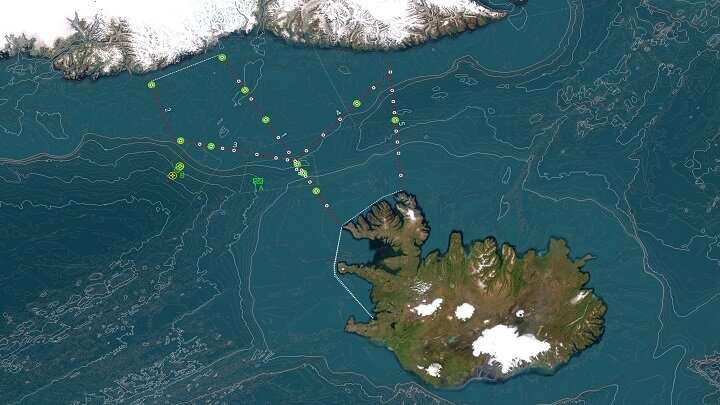

This phenomenon plays a decisive role in the Atlantic thermohaline circulation—and therefore in the global climate—and is key to the functioning of the deep-sea ecosystems in the area. Although this dense water overflow is and has been intensively studied by the scientific community from the point of view of physical oceanography, there are key aspects that are still unknown and will be addressed in the FAR-DWO oceanographic campaign. The project, which will be carried out from July 19 to August 12 aboard the oceanographic ship Sarmiento de Gamboa (owned by the Spanish National Research Council), is led by Professors David Amblàs and Anna Sanchez-Vidal, from the Consolidated Research Group on Marine Geosciences of the Faculty of Earth Sciences of the University of Barcelona (GRCGM-UB).

Exploring the lesser-known side of the Denmark Strait undersea waterfall

"To date, the hydrodynamic characteristics of this large underwater cataract had been studied, but in FAR-DWO we intend to explore aspects that are still unknown, such as its capacity to transport sediments and modify the relief and the influence of topography on its propagation," say David Amblàs and Anna Sanchez-Vidal, members of the Department of Earth and Ocean Dynamics at the UB. "FAR-DWO will analyze for the first time the hydrographic and sedimentological variability from the sampling and observation of the water column and the sediment and relief of the seafloor during the campaign, with the deployment of two instrumented lines at great depth that will record current information for a whole year, until September 2024, when they will be recovered."

A phenomenon described extensively and pioneeringly in the north of the Catalan coast

Undersea waterfalls are one of the most fascinating phenomena in modern oceanography. Their impacts on the seafloor were unknown until they were first described in the northern coast of Catalonia, in the northwestern Mediterranean, in a scientific paper led by GRCGM-UB researchers (Nature, 2006). After that study, the GRCGM-UB has been a pioneer in monitoring research—with lines instrumented with sediment traps, current meters and temperature sensors—of dense water cascades both in the Cap de Creus canyon and in different polar areas.

The phenomenon of dense water overflow is particularly intense in the Arctic and Antarctic. "The poles are the regions where most of the dense water masses—generated by the formation of sea ice at the surface—eventually reach the global ocean floor. The polar areas are like the heart of the oceanic circulatory system: they pump cold, dense water into the great oceanic troughs through the heartbeats made by overflows of dense water," says David Amblàs.

How does climate change affect undersea waterfalls?

There is increasing evidence of the effects of global change on the phenomenon of submarine waterfalls. "A good example is on the Catalan coast, where the decrease in the number of tramontane days in winter in the Gulf of Lion and north of the Catalan coast is causing a weakening of this oceanographic process, which is decisive in regulating the climate and has a great impact on deep ecosystems," says Anna Sanchez-Vidal.

In polar areas, a greater influx of freshwater and less sea ice formation will also mean a reduction in the volume of dense water moving towards lower latitudes. "This process has several effects on global ocean circulation that are of concern to the scientific community, as reflected in the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change", says Anna Sanchez-Vidal.

The researchers note that, during the FAR-DWO campaign, they want to "take the knowledge about their behavior and the impacts they generate one step further." "For this reason, we will intensify and expand the monitoring effort acquired so far in the Cap de Creus canyon, combining it with the monitoring of the waterfall in the Denmark Strait," they say. "These two study areas—one temperate and the other polar—provide an ideal frame of reference to investigate the propagation of these currents, the associated biogeochemical fluxes and their imprint on the seafloor and sedimentary record, as both marine areas are major players in the global ocean thermohaline circulation system," they add.

"Observational data from both marine areas will be combined with a numerical hydrosedimentary model, which will provide for the first time a quantification of the ability of marine cascades to shape the seafloor. The FAR-DWO project will also analyze the cascade variability in response to current and past climate changes. Through historical observations, review of oceanic and atmospheric models, and sedimentological and geochemical indicators in marine sediment cores, it will be possible to reconstruct the evolution of these oceanographic processes under different past climate scenarios," the team explains.

The FAR-DWO oceanographic campaign can be followed here.

Provided by University of Barcelona