Research on bee virus origins uncovers buzz-worthy breakthrough

European honey bees are the most common bee species used to produce honey globally. They have larger colonies compared to other bee species, produce more honey, are less aggressive, and excellent foragers.

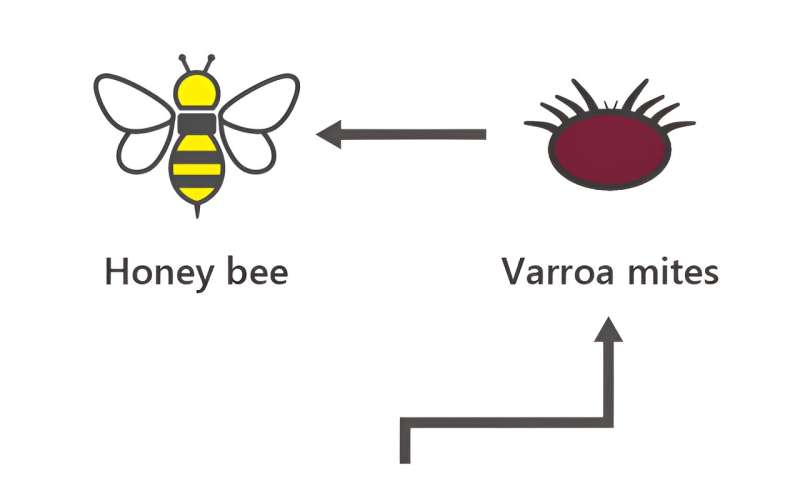

The spread of Deformed wing viruses (DWV) is one of the most important drivers in the decline in European honey bee populations worldwide. These viruses cause wing abnormalities and affect neurological functions in infected bees. They are transmitted to bees by parasitic mites called Varroa mites.

Nonno Hasegawa, a Ph.D. student at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST)'s Integrative Community Ecology Unit and Dr. Maeva Techer, a former researcher at OIST, have collaborated with other scientists and coauthored a recently published paper on the evolutionary history of the Deformed wing virus in European and Asian honey bees.

Their article titled "Evolutionarily diverse origins of Deformed wing viruses in western honey bees" was published in the journal PNAS. Findings show that one of the most common strains of the virus, DWV-A, originated in Asia and not Europe, as previously suggested.

"European honey bees were introduced to Asia and other parts of the world and became widely used in horticulture because they are more productive for beekeeping than the endemic Asian honey bees. These are an invasive species of bees and that's a problem because when we bring different species to areas where they do not naturally occur, we are increasing the risk of diseases spreading in both native and invasive species," Nonno explained.

When European honey bees were introduced in Asia, the Varroa mites switched hosts, moving from the original native host, the Asian honey bees, to the new more susceptible host, the European honey bees, and transmitting DWV to the European honeybees in the process.

"The Deformed wing virus is easy to identify in the field because you can clearly see that the wings of infected bees are deformed. The infected bees can also become disorientated when they move around. Eventually, when a significant number of bees become infected, the colony may be unable to sustain itself due to a shortage of foragers. This can result in an unhealthy hive that may gradually die off. Deformed wing viruses are currently thought to be one of the key drivers causing the decline of European honey bee populations worldwide," Nonno added.

The original hosts, Asian honey bees, have had millions of years of coevolution with the parasitic Varroa mites. They have adapted to the mites in several ways such as physically removing them and removing dead and infected bees from the hive.

European honey bees, on the other hand, have had much less time to develop ways to fight the virus, making them more vulnerable.

The researchers focused on two main strains of the Deformed wing virus, DWV-A and DWV-B. They used RNA sequencing—a method to analyze the presence and quantity of RNA in a biological sample and analyzed varroa mites collected from different host bees from 56 sites around the world to uncover the presence of viruses.

Because the viruses the mites carry are mostly RNA viruses, RNA sequencing allows researchers to analyze which viruses are present in each sample. By having samples that vary spatially and temporally, they were able to statistically predict the origin of DWV-A.

They found that the DWV-A strain did not originate in Europe but in Asia, in contrast to what researchers previously believed. This suggests that DWV-A was present in Varroa mites before European honey bees were introduced to Asia. This strain of the virus then spread worldwide after it was transmitted to European honey bees by the mites.

The presence of Varroa mites carrying the virus and the switch to a new host likely drove the increase in DWV-A infections worldwide.

In contrast to DWV-A, they found no strong evidence that the DWV-B strain levels were affected by the Varroa host switch at a global level. DWV-B was first detected in 2001, decades after DWV-A first appeared, suggesting that it was either a virus new to European honey bees or was limited to specific locations in the past and not detected until later.

It is possible that the DWV-B strain was already present in some populations of European honey bees before they arrived in Asia, and the Varroa mites provided a new mode of transmission. Alternatively, the DWB-B strain may have been acquired from another host after the Varroa host switch or through contamination of laboratory specimens used in research studies.

Interestingly, there is an increase in DWV-B in Europe and North America, and an increase in the spread of Varroa mites in these regions at the same time. The scientists state that future work should investigate the origins of DWV-B to better understand how new viruses can enter the Varroa-bee ecosystem.

Nonno stressed the importance of providing suitable habitats for other key pollinators. "While European honey bees are good foragers and can help with mass pollination, they can outcompete local pollinators such as bats, butterflies, moths, and other bees," she explained. "Monoculture, the practice of growing a single crop in a large area, can have negative impacts on pollinators and the environment. We should preserve local pollinators by planting indigenous plants and avoid the introduction of invasive species."

The findings from this study can provide us with a deeper understanding of how bee viruses originate and spread, and how to manage them.

More information:

Nonno Hasegawa et al, Evolutionarily diverse origins of deformed wing viruses in western honey bees, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2301258120

Provided by Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology