Scientists from St Petersburg University discover larvae of marine parasitic worms with division of labour

Zoologists from St Petersburg University and the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences together with their colleagues from Austria, Japan, Sweden and the U.S. have discovered a new form of parasitic worms from Trematoda class. This form is an aggregate of polymorphic larvae adjoined together by their tails.

The study of biodiversity in zoology is one of the most pressing scientific challenges in the modern world. However, marine fauna has always been most extensively studied in the North Atlantic, while marine animals, and especially parasites, are understudied in Southeast Asia.

One such parasite was seen off the shores of Okinawa Island by the famous Japanese underwater photographer and diver Ryo Minemizu. He photographed and later caught a small animal that looked like a ball with a couple of dozens of outgrowths, due to the active movement of which the organism moved. Despite the fact that Ryo Minemizu had been photographing the inhabitants of the underwater depths for many years, that was the first time he had seen such an animal. That is why he sent this sample to Igor Adameyko, a researcher at the Medical University of Vienna. He, in turn, showed the find to zoologists from the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Science and St Petersburg University. They recognised the animal found off the shores of Okinawa Island as the larvae of parasitic worms.

Together with our colleagues, we managed to study the structure of this specimen in detail, determine its taxonomic affiliation, and even propose an explanation for its strange appearance, which we had not seen before. This animal turned out to be an aggregate of cercariae, one of the larval stages of trematodes.

Darya Krupenko, co-author of the research, Assistant Lecturer in the Department of Invertebrate Zoology, St Petersburg University

Trematodes are parasites with a complex life cycle, during which they can change several hosts and morphologically contrasting stages. For example, an adult worm parasitises a vertebrate animal and lays eggs that are released into the external environment. The larva then emerges from the egg and finds a first intermediate host, usually a mollusc. Inside the mollusc, the trematodes actively reproduce and feed on its sex gland and liver, after which the cercariae appear. This is the next stage of the trematode life cycle, which has been identified by the zoologists from St Petersburg University.

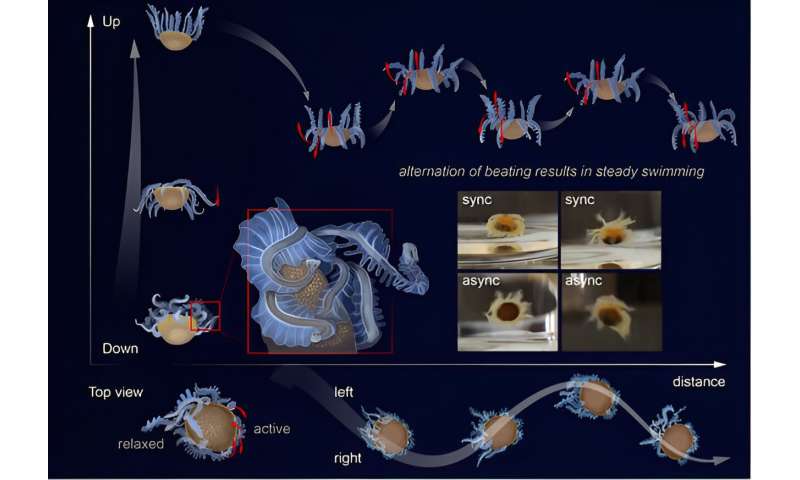

Cercariae come in many forms—some are large and have large tails, some swim actively, others attach themselves to the substrate and wait. All this is done so that the cercariae can get the next host: a fish, crayfish or other invertebrate. The cercariae either actively invade the second intermediate host, or it unwittingly eats them, and then the parasite begins to feed at its expense. However, the parasite only enters the final host after feeding on a second intermediate host—a small marine invertebrate that is attracted to the cercariae.

In order for the second intermediate host to find and infect the cercariae by eating them, some cercariae mimic the usual food of the desired fish species by the shape of their body and tail, and some can even adjoin by their tails to build a large and conspicuous aggregate for marine wildlife. Such cercariae are called zygocercous. This not only makes it easier for the parasites to find a second intermediate host, but also makes it easier for them to reproduce later, inside the final host.

'The specimen found in Okinawa Island was exactly like this. It is a large number of cercariae that are intertwined with their tails. However, the most interesting thing is that this was the first case when two different types of cercariae adjoined in such an aggregate, so the find can be called a polymorphic swimming colony. Moreover, within this colony we can observe a fundamental division of functions: conventionally we called the two types of cercariae "sailors" and "passengers". The "sailors" are larger, and it is they that enable the aggregate to move, while the "passengers" are inactive until they fall into a new host. What happens to the "sailors" after infection of the second intermediate host is not entirely clear, and it is possible that they cannot continue to live in it. So, it seems that the "sailors" sacrifice themselves so that the "passengers" can continue their development,' explained Darya Krupenko, Assistant Lecturer in the Department of Invertebrate Zoology at St Petersburg University.

Molecular analysis of this specimen enabled the University's zoologists to identify it as belonging to the genus Pleorchis. The researchers are confident that there is definitely more than one species of these polymorphic cercariae. Additionally, many questions remain unresolved about the life cycle of these trematodes, so the zoologists plan to continue investigating these animals in future.

More information:

doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.08.090

Provided by St. Petersburg State University