University team taps unused fiber cables for earthquake detection and urban monitoring

After a devastating childhood earthquake in the Gujarat region of her home country of India, Jyoti Sharma often thought about creating an early earthquake warning system. Now a postdoctoral fellow at SMU, she is working with SMU professor Stephen Arrowsmith to transform the University's network of unused telecommunications and computer fiber into a sophisticated seismic monitoring system.

Underneath SMU's well-groomed lawns and red brick buildings are thousands of unused fiber optic cable—"dark fiber"—earmarked for future use. Working with SMU's Office of Information Technology, Sharma and Arrowsmith are exploiting imperfections in the communication fibers to detect seismic vibrations, both near and far.

It's called Distributed Acoustic Sensing—or DAS, for short. Imagine being able to listen to everything happening along an extensive fiber network. DAS makes this possible, sending laser pulses through the fibers with small portions of that light being scattered back to an interpretive device called an interrogator.

The data collected by the DAS interrogator shows when the fiber is compressed or stretched due to earthquake-driven shaking or small vibrations created by everyday traffic.

Traditionally, scientists have used seismometers to measure vibrations in the Earth's surface. SMU faculty members use seismometers for everything from measuring regional earthquake activity to monitoring compliance with nuclear test treaties. Connecting DAS to dark fiber could expand seismic monitoring far broader than what is currently covered by seismometers and can be readily used in densely urban areas.

Sharma, who is affiliated with the Institute of Seismological Research in Gujarat, India, had met Arrowsmith in an online seminar during the COVID-19 pandemic and was inspired by his efforts to use DAS for seismic detection.

"I definitely plan to use DAS in the seismic active zones of India, particularly in Kutch, Gujarat, which experiences continuous seismic activity," said Sharma.

"DAS offers ease of deployment in various geological terrains, enables us to understand how much fibers strain in demanding environments, and holds significant potential in early warning systems by detecting even the smallest seismic and acoustic signals."

Arrowsmith sees DAS not as a replacement for traditional seismometers but as a valuable complement. Researchers have grappled with the unique challenge of processing DAS datasets, which differ from the recordings captured by seismometers and are much larger. Sharma is utilizing SMU's high-performance computing cluster to handle the massive volume of data.

-

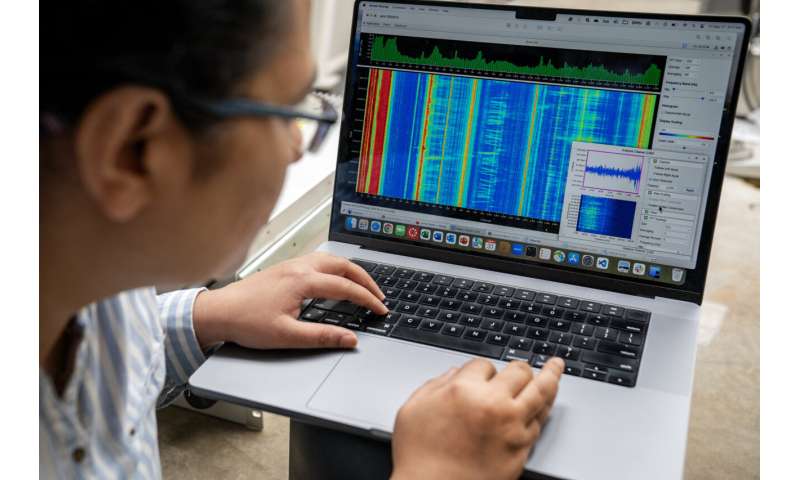

Sharma reads data collected by the DAS interrogator. Credit: SMU -

Arrowsmith and Sharma read data collected by the DAS interrogator on the SMU campus. Credit: SMU

"Having access to dark fiber and a computer that can run this much data puts us in a good position to understand DAS for future uses," said Arrowsmith. "There's a push in Earth Sciences for more focus on environmental and urban seismology, and DAS allows SMU to do research in those spaces."

For Sharma, her childhood hope of creating a new early earthquake warning system is becoming a reality. She envisions a future where DAS plays a much larger role in mitigating seismic activity's impact.

Provided by Southern Methodist University