From crocodiles to krill, a warming world raises the 'costs' paid by developing embryos

Apart from mammals and birds, most animals develop as eggs exposed to the vagaries of the outside world. This development is energetically "costly." Going from a tiny egg to a fully functioning organism can deplete up to 60% of the energy reserves provided by a parent.

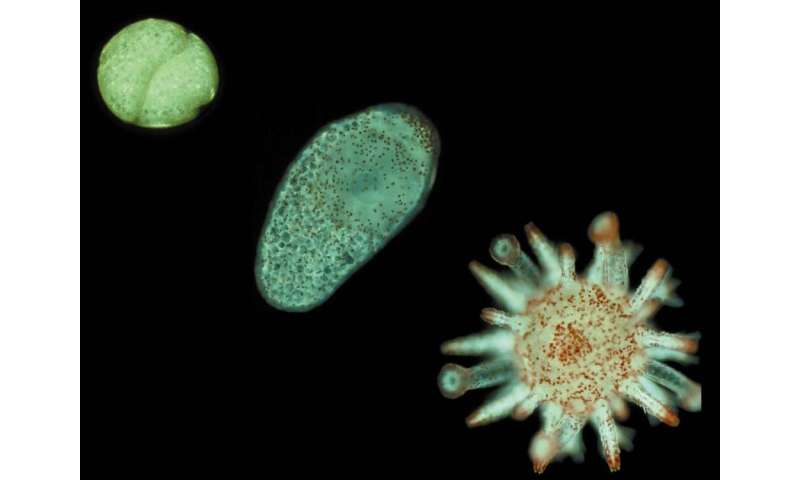

In cold-blooded animals such as marine invertebrates (including sea stars and corals), fish and reptiles, and even insects, embryonic development is very sensitive to changes in the temperature of the environment.

Thus, in a warming world, many cold-blooded species face a new challenge: developing successfully despite rising temperatures.

For our research, published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution, we mined existing literature for data on how temperature impacts the metabolic and development rates of 71 different species, ranging from tropical crocodiles to Antarctic krill.

We found over time, species tend to fine-tune their physiology so that the temperature of the place they inhabit is the temperature needed to minimize the "costs" of their embryonic development.

Temperature increases associated with global warming could substantially impact many of these species.

The perfect weather to grow an embryo

The energy costs of embryonic development are determined by two key rates. The "metabolic" rate refers to the rate at which energy is used by the embryo, and the "development" rate determines how long it takes the embryo to fully develop, and become an independent organism.

Both of these rates are heavily impacted by environmental temperature. Any change in temperature affecting them is therefore costly to an embryo's development.

Generally, a 10°C increase in temperature will cause an embryo's development and metabolic rate to more than triple.

These effects partially cancel each other out. Higher temperatures increase the rate at which energy is used (metabolic), but shorten the developmental time.

But do they balance out effectively?

What are the costs?

For any species, there is one temperature that achieves the perfect energetic balance between relatively rapid development and low metabolism. This optimal temperature, also called the "Goldilocks" temperature, is neither too hot, nor too cold.

When the temperature is too cold for a certain species, development takes a long time. When it's too hot, development time decreases while the metabolic rate continues to rise. An imbalance on either side can negatively impact a natural population's resilience and ability to replenish.

As an embryo's developmental costs increase past the optimum, mothers must invest more resources into each offspring to offset these costs.

When offspring become more costly to make, mothers make fewer, larger offspring. These offspring start life with fewer energy reserves, reducing their chances of successfully reproducing as adults themselves.

Thus, when it comes to embryonic development, higher-than ideal temperatures pack a nasty punch for natural populations.

Since the temperature dependencies of metabolic rate and development rate are fairly similar, the slight differences between them had gone unnoticed until recently.

Embryos at risk

For each species in our study, we found a narrow band of temperatures that minimised developmental cost. Temperatures that were too high or too low caused massive blow-outs in the energy budget of developing embryos.

This means temperature increases associated with global warming are likely to have bigger impacts than previously predicted.

Predictions of how future temperature changes will affect organisms are often based on estimates of how temperature affects embryo survival. These measures suggest small temperature increases (1°C-2°C) do not reduce embryo survival by much.

But our study found the developmental costs are about twice as high, and we had underestimated the impacts of subtle temperature changes on embryo development.

In the warming animal kingdom, there are winners and losers

Some good news is our research suggests not all species are facing rising costs with rising temperatures, at least initially.

We've created a mathematical framework called the Developmental Cost Theory, which predicts some species will actually experience slightly lower developmental costs with minor increases in temperature.

In particular, aquatic species (fish and invertebrates) in cool temperate waters seem likely to experience lower costs in the near future. In contrast, certain tropical aquatic species (including coral reef organisms) are already experiencing temperatures that exceed their optimum. This is likely to get worse.

It's important to note that for all species, increasing environmental temperature will eventually come with costs.

Even if a slight temperature increase reduces costs for one species, too much of an increase will still have a negative impact. This is true for all the organisms we studied.

A key question now is: how quickly can species evolve to adapt to our warming climate?

More information:

Marshall, D.J., Pettersen, A.K., Bode, M. et al. Developmental cost theory predicts thermal environment and vulnerability to global warming. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 406–411 (2020). doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1114-9 , www.nature.com/articles/s41559-020-1114-9

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

This story is part of Science X Dialog, where researchers can report findings from their published research articles. Visit this page for information about ScienceX Dialog and how to participate.